Partitioning Hypergraphs in DQC

15th of January 2026

Hypergraphs are a natural way to encode multi-qubit dependencies. They have been widely used in DQC research to abstract and partition quantum computations. This partitioning has been done through heuristics designed to tackle the hypergraph partitioning problem. In this post I will give a quick overview of the problem, its relevance to DQC, and some of the most popular heuristics used to tackle it.

Hypergraph: A generalization of a graph where edges (called hyperedges) can connect any number of nodes, not just two. A hyperedge can link two, three, four, or more nodes simultaneously. You can think of a hypergraph as a collection of groups, where each hyperedge defines one group of interconnected nodes.

This way of modeling distributed quantum computations has intertwined hypergraph theory with the field of DQC. In this blog post I will dive into hypergraph partitioning heuristics designed to tackle the hypergraph partitioning problem, which is a very well known NP-hard problem in computer science, but may not be the best fit for DQC.

Hypergraphs in DQC

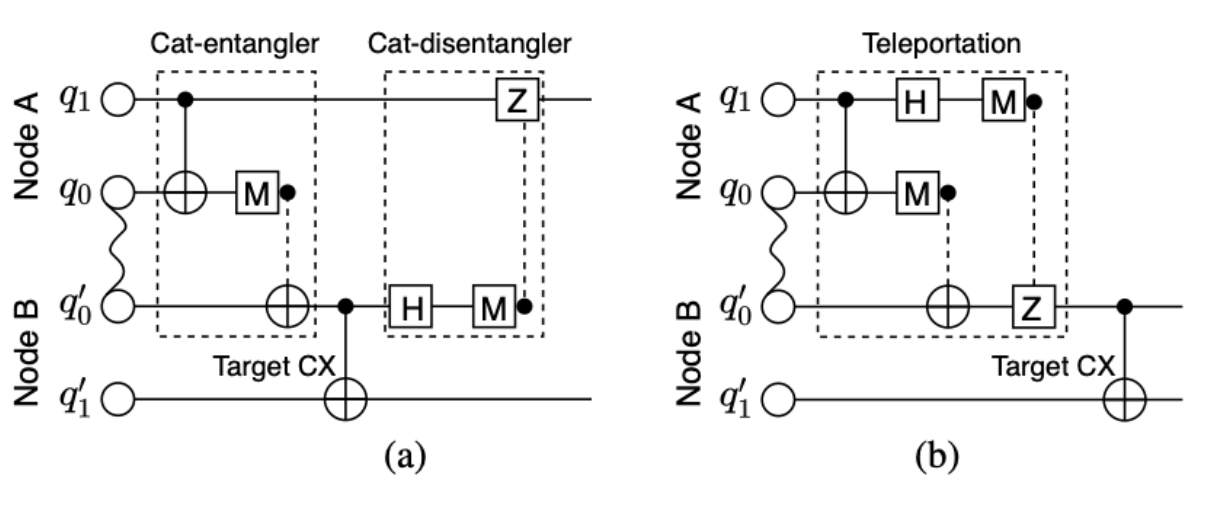

Hypergraph-based representations came into the Distributed Quantum computing sphere back in 2018 through Martinez & Heunen's Automated distribution of quantum circuits via hypergraph partitioning. Hypergraphs serve as a very natural abstraction of the dependencies that must be maintained across sub-workloads of a larger computation, which is a crucial part of the DQC problem: how do I cut up my computational pie such that my cut up pie is equivalent to my original? The original proposal was to represent qubits as the items/nodes of a hypergraph and quantum gates as the hyperedges connecting these qubits. Meaning that the computational dependencies generated multi-qubit gates, which are in essence entangling gates, were now encoded into this abstraction.Communication primitive (DQC): A communication primitive can be thought as the implementation strategy for non-local gates. It defines the translation from a multi-qubit gates acting between QPUs into a series of quantum operations that can be executed within the relevant devices, using the quantum network, to implement an equivalent non-local operation. Two of the most common communication primitives are the teleportation-based protocol (TP) and the cat-entangler based protocol (CAT):

Hypergraph partitioning: the problem

The hypergraph partitioning problem is probably one of the most investigated NP-hard problems in computer science. At its core, the problem consists of dividing the nodes of a hypergraph into disjoint subsets (partitions) such that:- The number of hyperedges that connect nodes in different partitions (the cut size) is minimized.

- While ensuring that the partitions are balanced in size (i.e., each partition has roughly the same number of nodes).

NP -> heuristics, and good heuristics are expensive. In distributed systems today (coming back to the classical world), you need to make partitioning decisions quickly, making complex heuristics prohibitive. Classical distributed systems researchers often dealt with highly dynamic messy scenarios where the hypergraph structure changes rapidly, making the overhead of re-partitioning exceed any benefits from better partitioning. Hypergraph partitioning is just not the way for classical distributed systems today, but we can perhaps all agree that DQC today is far from that setting. Its messy, but for other reasons. Making hypergraph partitioning a more viable option, at least in the short term.

Yet, I don't want to be too discouraging of hypergraph abstractions in DQC. They are a very natural way to represent crucial dependencies in distributed quantum computations, which may not exist in the same form in classical distributed systems. In classical systems you have what we could call "classical dependencies", meaning you require the result from an operation before you complete the next. These can be modeled with graphs, as pairwise dependencies, and fit nicely in queueing systems. In DQC however, you have "quantum dependencies", meaning that certain operations require entanglement. These dependencies require both the previously mentioned classical dependency as well as the consumption (and thus availability) of a specific resource (entanglement). They are not pairwise, as entanglement can exist between multiple qubits (GHZ states, W states, etc); and furthermore they are absolutely everywhere. Hypergraphs may be the way to go in DQC if we're talking about taking a massive monolithic circuit and mapping it down to a network of collaborating devices. Note that although this is my area of work at the moment, it doesn't have to be the way forward, and it certainly isn't how we run things in classical distributed systems today. (I keep talking about classical systems because they are the precursor to all of this DQC malarkey.)

That being said, although I do have a soft spot for hypergraph abstractions, THE hypergraph problem will see the wrath of my hammer. It's first goal is all good and dandy, we do want to minimize inter-partition hyperedges, they are expensive, consume resource, and introduce noise, all generally bad things.

But "balancing partitions"?!?!?! Why on earth do we care about balancing partitions? Perhaps this hatred comes from my innate abuse of any computational resource I am presented with.

- Minimizing the overall resource consumption (entanglement, qubits, time).

- Maximizing the overall fidelity of the distributed computation.

- Actually respecting the hardware constraints of the devices.

TLDR: the hypergraph partitioning problem is not DQC, its a nice starting point, lets get over it.

Nonetheless, the point of this post is to explore hypergraph partitioning in DQC, so with my rant out of the way, let's talk about some of the cool maths and cs behind hypergraphs in DQC.

Heuristics: State of the art

NP-hard problem implies heuristics.1) Greedy and random: the simple path

The Simplest Solution is the Best Solution ~ Occam’s RazorGreedy and random methods operate directly on the hypergraph without any nonsense (what I mean by "nonsense" will become clear later). They're fast, straightforward, and surprisingly effective for quick-and-dirty partitioning when you don't have time for the computational equivalent of a five-course meal.

Greedy algorithms follow the age-old strategy of "make the best choice right now and hope for the best later". In hypergraph partitioning, this means starting with to "eat" (in fancy talk we would call this seed) a node and growing partitions by repeatedly eating the next/closest node that minimizes some cost metric (in this case number of cut hyperedges). This method is as fast as you're going to get and works ridiculously well especially when hypergraphs have strong locality or community structure. In my own work I've seen it outperform (KaHyPar - the favourite DQC baseline, and an incredible multilevel partitioner) on a stupid amount of real circuits (fake/artificially created circuits tend to not behave the same as "real circuits", meaning circuits actually created to implement quantum algorithms that present advantages), to the point in which I am not too convinced that it shouldn't be the default baseline for DQC hypergraph partitioning. Its speed, performance, and implementation simplicity make it in my eyes an unironic contender for the long game in this field. The "meat" of the game here is that first seeding, it is not an uncommon assumption in heuristic hypergraph methods as you will soon see.

Random partitioning is exactly what it sounds like. U just randomly assign nodes to partitions. Again, stupid as it may sound, it's actually a legitimate baseline and sometimes used as an initial solution for more sophisticated methods. Plus, when combined with refinement techniques, random starting points can actually lead to surprisingly good results. And what beauties quantum computers are at generating randomness, are they not?

If you want to play around with greedy methods, most hypergraph libraries include basic implementations. For spectral methods, check out tools like NetworkX (for graphs) or implement your own using numpy/scipy for the eigenvalue computations.

2) Iterations: local search

With simple but efficient out of the way, let's build our way into obscure complex stuff, starting at the simplest row: local search methods. Local search is all about starting with a solution (could be random, could be greedy, nobody seems to care even though it actually matters quite a lot) and then iteratively improving it by making small tweaks. It's like being a gen-Z and renting your first room (because houses are not gonna happen), then slowly upgrading the furniture over a few years until you have a Pinterest-worthy space (or a compromise). These methods are the workhorses of hypergraph partitioning and show up everywhere, especially as refinement steps in more complex algorithms.The absolute classic here is FM (Fiduccia-Mattheyses). FM works by maintaining a priority queue of nodes sorted by their "gain" (how much moving a node to another partition would improve the cut). At each step, you pick the node with the highest gain, move it, lock it (you don't get to move it again in this pass), and update the gains of neighboring nodes. You keep going until all nodes are locked, then you roll back to the best solution you saw during the pass. At that point you unlock everything and do it all over again until you stop seeing improvements.

What makes FM clever is that it allows temporary bad moves, you might make the cut worse for a bit, but the algorithm can escape local minima this way (at least theoretically). It's actually quite effective and forms the basis for most modern refinement algorithms.

For multiple partitions (k-way partitioning where k > 2), you've got k-way FM extensions that generalize the idea. Instead of just moving nodes between two partitions, you consider all possible target partitions for each node and pick the best one. It's more complex but handles the multi-way case directly without having to do recursive bisection.

There's also Kernighan-Lin, which is an older algorithm from the 1970s that works similarly but swaps pairs of nodes between partitions instead of moving single nodes. It's slower than FM but sometimes finds better solutions because it considers pairwise moves.

Most serious hypergraph partitioning tools include FM-style refinement. KaHyPar uses heavily optimized FM variants, and you can find standalone implementations in libraries like hMETIS.

3) Spectral methods: the global view

Local methods tweak a partition by moving a few nodes at a time. They are fast and myopic. Global methods do the opposite. They try to extract a global pattern first, and then cut along that pattern. A few variants exist ( flow and cut relaxations, global inference, etc), but I am just going to focus on spectral methods, to give you an intuitive idea of how global approaches work, and perhaps partially answer the question of whether we can hypergraph-partition with quantum computers (we probably can, it is probably not worth it, but hey I am about to use the word eigenvector!).Hypergraphs do not have a single universally agreed Laplacian. As a result, “spectral hypergraph partitioning” is really a family of choices. You first decide how to turn the hypergraph into something spectral methods can act on. Common options include:

- Clique expansion: turning each hyperedge into a clique in a graph. This often leads to massive graphs and tends to over-penalize large hyperedges.

- Star expansion: building a bipartite graph between nodes and hyperedges. This grows only linearly in the number of incidences, but you are now partitioning a different graph, and mapping the result back is not always clean or structurally meaningful.

- Direct hypergraph Laplacians: defining operators directly from the incidence structure. These avoid blow-ups, but introduce normalization choices that materially affect the result.

4) Multilevel: the fancy pants solutions

Multilevel methods are where things get sophisticated. These are the state-of-the-art approaches that dominate hypergraph partitioning records and get used in real-world applications. The core idea is quite simple: if your hypergraph is too big and messy to partition directly, make it smaller first, partition that, and then carefully expand back to the original size while refining your solution.The entire thing relies on this smaller partitioning being a good solution, but if you believe this (which based on their performance seems to be correct), you've just got to follow three steps:

- Coarsening: Repeatedly merging nodes together to create smaller versions of your hypergraph. Common strategies include matching (pair up similar nodes and merge them) or heavy-edge coarsening (merge nodes connected by heavy hyperedges).

- Initial partitioning: Once the hypergraph is small enough (this is kind of arbitrary), you partition it using a simpler method (any of the above, FM and greedy are popular choices). This gives you the baseline solution.

- Uncoarsening with refinement: Now you've just got to reverse the coarsening process. But you get to make some smart decisions along the way. At each level, you can "unmerge" nodes and use a local search method (usually FM) to improve the partition, meaning that you remap your super-node's nodes somewhat "smartly". When you've made your way back, you're done.

As I said earlier, solving the problem at a coarse level seems to give us a good global view of the structure, and the further refinement at each level handles local sub-optimisations. These methods basically sketch first, and paint later. They include:

KaHyPar (Karlsruhe Hypergraph Partitioner), I did say we would get to him. KaHyPar (kahy for friends) is THE partitioner today. It's fast, produces cheap partitions, and is actively maintained. Under the hood, KaHyPar uses an n-level hypergraph partitioning strategy, where nodes are contracted very gradually, preserving structural details, followed by adaptive (meaning it dynamically adjusts its strategy based on the contextual cost/structure it sees) local refinement during uncoarsening. This allows it to optimize not just simple cut counts, but more expressive objectives such as connectivity and weighted communication costs. The community behind it has made multiple versions (KaHyPar-CA, KaHyPar-K, etc.) optimized for different scenarios. Check it out at kahypar.org and their GitHub repo. This is the most likely to be the baseline in any DQC hypergraph partitioning work today. If you want to have a go at playing with it, I've recently written up a quick guide for the Python binding installation: see guide.

hMETIS is an older classic that pioneered many multilevel techniques. Metis is basically KaHyPar but for graphs, and hMETIS extended metis' ideas to hypergraphs. Its approach relies on more aggressive multilevel coarsening, rapidly collapsing nodes, followed by FM-style greedy refinement to minimize hyperedge cuts. This makes hMETIS fast and robust, but unlike KaHyPar it's not very flexible and commits to structural decisions very early. Still widely used and cited, it is not as actively developed (to my knowledge). Learn more at UMN's METIS page.

5) Geometric: for the maths enthusiasts

Geometric methods are a different beast. They only work when your hypergraph nodes have associated coordinates in some metric space (physical locations, embeddings in vector space, connectivity topology in a quantum chip/network, timesteps, ...). When applicable, they can be extremely fast and produce intuitive partitions that respect spatial locality.The classic approach is Recursive Coordinate Bisection (RCB). You pick a coordinate dimension (x, y, or z), find the median value, and split the nodes into two groups based on that median. Easy peasy right? You then recursively apply this to each partition until you've got the number of partitions you want. It's FAST (we're talking O(n log n)) and works very well when your problem has strong spatial structure.

For example, if you're partitioning a mesh for finite element analysis, nodes represent physical points in space. RCB will naturally group nearby points together, which is exactly what you want for minimizing communication in parallel scientific computing.

Space-filling curves enable another strategy. A space-filling curve is basically a continuous curve that passes through every point in a multi-dimensional space. Examples include Peano, Hilbert and Morton (Z-order) curves. They basically enable the mapping of multi-dimensional space onto a one-dimensional line while (approximately) preserving locality.

Now these methods only care about geometry. They completely ignore the actual hyperedge structure, and only use node coordinates. This can be a blessing (cause it's super fast), but it will be a curse if the geometry of your hypergraph doesn't align with the connectivity. They're often used as a very fast initial solution or for problems where geometry genuinely dominates the structure.

6) Metaheuristics: black box magic

Metaheuristics are our final wild card. They can tackle any problem as long as you can define a cost function. They're "meta" because they're higher-level (not because of facebook), meaning they guide the search process rather than being specific algorithms. As per the title, this includes our black boxes (ML, genetic algorithms, etc).Genetic Algorithms (GAs) were the first metaheuristic to be tested in DQC. Before AI exploded, I like to think they were every tech bro's favorite way to play god. The idea is you're mimicking evolution by having a population of candidate solutions that evolve over time. They evolve through crossover, mutations and natural selection. For hypergraph partitioning, each "individual" is a partition, and the fitness function typically combines cut size and balance violations.

GAs have the power to escape local optima by exploring many different regions of the solution space simultaneously. Which is lovely, but they're slooooow, so rarely used in production systems.

Simulated Annealing is probably a more familiar name to the quantum crown. The idea here is we start with a random partition at high "temperature," repeatedly make random modifications, and accept worse solutions with some probability that decreases over time (we're "cooling"). This method also has the power to escape local optima early on, but it eventually settles into a good solution as the temperature drops. It's simpler than GAs but it still slow and requires careful tuning of the cooling schedule.

Ant Colony Optimization is inspired by how ants find paths to food. Virtual ants traverse the hypergraph, leaving "pheromone trails" that influence future ants. It's once again computationally expensive and doesn't exploit problem structure the way specialized algorithms do.

I should have probably titled this section "Ideas from nature, expensive and slow but cool sounding". The fundamental issue with metaheuristics for hypergraph partitioning is that they're too general: they don't leverage the specific structure of hypergraphs the way multilevel methods or FM refinement do. You're trading specialized efficiency for broad applicability. They can work, and might even find interesting solutions in weird corner cases, but for the standard problem you're almost always better off with multilevel methods.

That said, metaheuristics shine when you have additional constraints/objectives that break the standard formulation—things that are hard to incorporate into traditional algorithms. For instance if you care about heterogeneous QPU capacities (that's crazy, who would care about that), asymmetric communication costs, time-dependent constraints, or multi-objective trade-offs that mix fidelity, latency, and cost into a single ugly objective, metaheuristics let you throw all of that into the fitness function and just… search.

Hypergraph partitioning (or perhaps its alternatives) in DQC today

I'm gonna do my best to give you a brief overview of alternative approaches to partitioning that have been developed specifically for DQC, but tbh if you're seriously exploring this go check "Review of Distributed Quantum Computing. From single QPU to High Performance Quantum Computing" (paper). section 4.1.1. for a great overview (from 2024 so perhaps slightly out of date). An important and very irritating note before we start: there are little to no cross-comparisons of these methods in the literature. They often use different benchmarks, metrics and comparison baselines. This makes it really hard to say which method is "best" in any meaningful way (it is possible, but it would take a lot of work - I would forever adore you though, and perhaps more importantly you would make an awesome contribution to the field).

Graph-based and reduced abstractions

Simplify and conquer! The reason why we build hypergraphs is mainly Toffoli gates (aka +2 qubit gates). Fun fact, these are often not natively supported in hardware! More often than not compilers decompose these multiway relationships into pairwise interactions (aka two qubit gates). So why not simplify and downgrade our hypergraphs into graphs? This leads to the graph partitioning problem, again NP-hard, but cheaper and faster to solve!

Assignment-based formulations

We have also seen people reframing partitioning as an assignment problem rather than a cut problem. A good example is the Hungarian Qubit Assignment (HQA) method introduced by Escofet et al.: qubits are assigned to QPUs by solving a weighted matching problem that minimizes communication cost. Which is conceptually very different from hypergraph partitioning, as:

- You do not explicitly minimize cut hyperedges.

- You directly optimize a cost matrix derived from circuit interactions and device constraints.

Advantages include the incorporation of:

- Heterogeneous device capacities.

- Asymmetric communication costs.

- Fixed hardware topologies.

Downsides include: common loss of the global structural view that hypergraphs provide.

Time-aware and slicing-based methods

Some works (ex) base themselves on the idea that not all dependencies exist at the same time. Gates are applied sequentially, they have timestamps/a temporal structure (from left to right in circuit diagrams). Time-sliced partitioning methods exploit this temporal structure by decomposing the circuit into temporal layers that are partitioned independently. This aims to reduce peak communication requirements at the cost of increased coordination; and often leads to fewer simultaneous non-local operations, which can be a big thing on real hardware (either due to resource costs - you may only have a limited number of entangling pairs available per time stamp - or error rates).

DAG-based stuff

In a similar vein to time-aware methods, some have replaced hypergraphs with circuit DAGs (Directed Acyclic Graphs).

Learning-based approaches

Of course reinforcement learning and ML-based methods have also been explored. These approaches treat partitioning as a sequential decision problem and learn policies that map circuit features to partitioning actions. They are appealing because they can, in principle, optimize arbitrary objectives and heterogeneous constraints (they are a type of metaheuristic). But they are expensive to train, hard to interpret and generalize poorly outside their training distribution. Due to the lack of cross-comparisons between methods, it's unclear whether all these cost even lead to an outperformance of the cheaper heuristics mentioned above. Yet (despite my personal skepticism about anything related to the word AI - do forgive me, it comes from ignorance and a dislike of snake oils which populate both the AI and quantum space), I don't think this avenue should be dismissed even if current models (which have gotten little attention) do not outperform simpler methods. In the classical world, learning-based methods have shown to be scalable and a reasonable path in related problems like graph partitioning and job scheduling (ex).

Where my own work fits

My own ongoing work with Hybrid Dependency Hypergraphs (HDHs) sits in between all of this. HDHs provide an abstraction that is:

- model-agnostic (meaning that it enables the abstraction of alternative quantum computational models such as MBQC (Measurement Based Quantum Computing), which are the native operation set for some quantum computers, namely photonic quantum computers, and are particularly natural for distributed settings since flying qubits are photons),

- explicit about both quantum and classical dependencies (enabling partitioning strategies that exploit classical control flow, which is typically far cheaper than consuming entanglement and dealing with quantum noise),

- directed (capturing the flow of information and dependencies, similarly to DAG-based representations, rather than treating the computation as an undirected connectivity problem).

The goal behind HDHs is to build a common ground on which partitioning methods can be explored and compared consistently. To support this, the project comes with a public database of HDHs and their partitions, covering various workload origins (different benchmarking suites) and partitioning strategies (greedy, KaHyPar, random) such that we can maintain a leaderboard of partitioning methods for DQC in a standardized reasonable abstraction.